1. Introduction

A Concerning Problem

In the effort to finish Bible translation in the remaining languages of the world that need it, it has become clear that addressing the non-use of local language (LL) translations cannot be ignored. For every translation that is finished but not used, two language communities are negatively affected—the one that did not use it or need it (through wasted time and effort), and the one that did need it and could have been served by those same funds and resources.

This research program is meant to address the question of non-use of LL Scripture on a broad scale—assessing translations via evidence-based studies in multiple countries and across multiple continents and looking at translations done via multiple methodologies and multiple agencies. In short, we want to: 1) have a better understanding of the extent of non-use of vernacular Scriptures worldwide, 2) have a better understanding of why this is happening. We begin this research program with this pilot study in Sulawesi.[1]

A considerable amount of scholarship has been done on the topic of Scripture use. Here is just a sample: T. W. Dye (1982; T. Dye 2009), Landin (1990), Harris (1997), Hill (2000), Griffis (2011), van den Berg (2020), and Ndemba (2025). The most cited of these studies has been Dye’s (2009) paper that identified 8 conditions that influence the use of local language Scriptures. While we agree with Dye that all 8 of these conditions do influence Scripture use, we believe that the broader ecological factors carry more weight than the methodological and spiritual ones and they are the hardest to change.

Dye himself stated that:

Although these eight conditions are alike in that each one must be adequate for Scriptures to be used, the things that can be done to improve them differ considerably. Appropriate Language and Freedom to Commit are affected by the whole socio-cultural situation and are difficult to change. (2009, 1)

The ‘appropriate’ language is a byproduct of a local language ecology, or what Dye refers to here as the ‘socio-cultural situation.’ A language ecology is a social context that includes all the languages in a given region, the communities who speak them, and the relationships that hold between them (Haugen 1972). Ecological factors can thus be viewed as ‘givens,’ characteristics of any specific language area that can only be changed by forces that alter those internal relationships.[2] Because of its ecological nature, the ‘appropriate language’ condition (the language a community perceives as most appropriate for the function of printed Scripture) is the one that we believe is the most critical of all of Dye’s 8 conditions. If translation is not in an ‘appropriate language’ for a given ecology, then all other factors become irrelevant. For that reason, we will focus on this one primary variable throughout this research without spending time discussing all the many secondary variables.

One of the main reasons a language is perceived by its community of speakers as ‘appropriate’ for a given function is if it has the appropriate level of prestige for that function. The principle that motivates this perception is known in sociolinguistics as ‘diglossia’. Diglossia is the underlying reason for a community perceiving a national language as more appropriate for literacy and Scripture than their local language. As a general sociolinguistic principle introduced by two of the pioneers of sociolinguistics, Ferguson (1959) and Fishman (1967), diglossia has become an accepted theory explaining much of language use in multilingual communities. Diglossia in a nutshell claims that multilingual communities will divide up the social functions common in their every-day lives, assigning the national languages to the more formal functions and the local language(s) to the more informal functions. As Scripture is commonly seen as a highly formal function for language, the presence of diglossia in an ecology would predict a preference for the use of NL Scriptures over LL Scriptures.[3]

This understanding of diglossia as the most critical factor in LL Scripture use is not unique to us — it has been included in Franks (n.d.) paper “Old habits die hard” (even though he does not refer to it as diglossia) and is part of the Scripture Engagement (SE) training course that has been built on Dye and others. Rick Nivens (p.c.), an SIL linguist and leader in SE training, points out that

“appropriate language” is the first thing to determine, and diglossia is part of that assessment. If a language doesn’t pass that “appropriate language” test, then all the other conditions are irrelevant.

To our knowledge no VSU research has yet been published that tests the ‘diglossia’ hypothesis as it relates to LL Scripture use. We believe it is time for that to be done and for BT agencies to be made aware of any correlations that might exist between diglossic ecologies and LL Scripture usage. [4]

Diglossia: A Compelling Solution

Ferguson (1959) introduced the idea of diglossia via his well-known study among majority languages and their related colloquial variants. Fishman (1967) built on Ferguson’s idea and extended it to include unrelated languages, or ‘broad’ diglossia. It is this later usage that we adopt here. Diglossia is a concept that helps us to understand how multilingual societies compartmentalize their language repertoire according to the domains most appropriate for each language. The assignment of a language to a domain is mostly influenced by the level of formality and prestige of the situation. Languages known as H varieties are associated with the more prestigious ethnic groups/members of a society and are assigned to more formal domains and functions, while languages known as L varieties are associated with less prestigious ethnic groups/members of society and are assigned to informal domains and functions. Once a language becomes established as the norm in one type of domain, using it in the wrong domain is not accepted as appropriate by the community. What has not been clearly established however, is how well this applies to the language choices of minority communities in the Scripture domain. Given the global phenomenon of multilingualism, it seems wise to test the effects of diglossia on Scripture choices.

The above principles become more pertinent when we realize that a change in the media used (orality vs literacy) is also a change of both domain and formality and can thus effect a change in language choice. While speaking mainly of indigenous language maintenance, Fishman’s (1965, 87) idea of ‘media displacement’ hinted at the focus of our current proposal. He believed that where literacy was acquired before interaction with an outside national language, such indigenous literacy may resist displacement by NL literacy. But where indigenous language literacy was introduced after the introduction of the national language, the persistence of such indigenous language literacy is less likely. The current proposal will build on both Ferguson’s notion of diglossia and Fishman’s idea of media displacement to search for answers to the use and non-use of minority language Scriptures today.

Sequencing of Translation

To research diglossia, we will focus on what we call the ‘sequencing of translation’ hypothesis. In practical terms it is the order in which different language translations are introduced into a particular community. This order sets the stage for the presence or lack of diglossia’s influence on Scripture use in a particular ecology over time. When an LL Scripture is translated before the local community is multilingual, that is a ‘pre-diglossic’ scenario. If there is any Scripture use, it will be in the LL. When the local community is multilingual and an existing NL Scripture is already in use when the translation of the LL Scripture arrives, that is typically a ‘diglossic scenario’. The presence of diglossia suggests that in those scenarios the strong tendency will be for the continued usage of the NL Scripture. Similarly, when the NL Scripture is introduced after the LL Scripture was used first, the ‘sequencing of translation’ hypothesis would predict that in most cases NL usage would eventually replace LL usage. But this hypothesis also predicts that LL first scenarios are the contexts that provide the greatest possibility for LL Scripture to defy diglossia and continue to be used after the arrival of NL Scripture. It’s the strong, pre-existing, association of an LL to the Scripture domain in the pre-diglossic phase that gives it a fighting chance for continued use during the diglossic phase. Thus, when we speak of the ‘sequencing of translation,’ we are speaking of particular consequences of the presence or absence of diglossia in the Scripture domain over time.

II. Research Questions

This research entails a phased project with multiple individual studies. This pilot is the first of those studies. The overall project has two objectives. First, each individual study in the project will describe the extent of both vernacular Scripture use and national language Scripture use in local language communities in a specific country or region. Secondly, the project as a whole will address the sequencing of translation hypothesis as it pertains to a wide collection of data from different countries. Our research questions based on those objectives are the following:

Research Question 1

What is the extent of local language Scripture use in each country or region surveyed?

Research Question 2

Do local language Scriptures become the/a normative text for public reading in public worship after national/regional language Scriptures have filled that role?

We will begin to address both of these questions in this Sulawesi study, but out final conclusions for Research question 2 will be addressed in a later paper.

Definition of Terms

A few definitions are in order:

Scripture – printed NT or whole Bible. In this study we are focusing primarily on printed Scripture. While we observed and noted the few times vernacular oral Scriptures were used during our survey, we are not making any claims about the use of oral Scripture, so it is possible that vernacular oral Scripture may not have these same limitations. However, we highly recommend that a similar study be conducted on the usage or non-usage of oral Scripture.

Normative text – by this we mean that it is the custom for a particular translation to be read publicly in a worship context. We are not looking for the occasional usage, but for usage that is the expected norm. If either the national or the indigenous language are new to the church domain they would not yet be considered normative (for this study, ‘new’ will be less than 6 months). If there is a mixing of both Scriptures being read out loud in church settings, we will report on the percentage of use of each. We will consider anything over 50% usage as normative use. If there seems to truly be a 50/50 mixing, both the national and the indigenous language would be considered normative.

Public reading in public worship – by this we mean that the Scripture is being read out loud by members of the local indigenous language community in places of group worship. This could be in the church setting, in home Bible studies, in prayer meetings, in outdoor religious celebrations, or any other place where members of the congregation gather to practice their faith in a public manner. By public reading we mean a practice by local church members and not outsiders (such as expat missionaries, national missionaries, or other members of a translation committee who may not be local). The tools we used did not focus on either private usage of Scripture or oral usage, such as listening to audio recordings of Scripture or the public singing of Scripture.

Why focus on Scripture in worship?

The most iconic and common domain of Scripture use is its public reading from a church pulpit once a week. We believe that this has historically been the expected use of vernacular Scripture by the Bible translation movement across the globe. A quote from Hill (2000) shows a common expectation that a successfully completed Bible translation would generally entail the reading of the vernacular Scriptures in public worship:

We can consider [the] Scripture use task finished successfully when…Church leaders use the existing translated Scriptures in situations where formerly they translated orally from a language of wider communication…If this goal is not met, we cannot say that we have succeeded in Scripture Use.

Exceptions as ‘Ecologies of Resistance’

Since ecologies can vary widely, we also predict that exceptions to the sequencing of translation hypothesis will exist in particular ecologies. We are referring to these as ‘ecologies of resistance’, as they are communities that are in some way resistant to the force of diglossia. So far, the types of exceptions reported to us appear to be limited and thus definable. They are defined by ecological characteristics that allow for the possibility of resistance to diglossia and provide more space for the LL—including LL Scripture use. These exceptions are thus extensions of the overall hypothesis. Barring such ecologies of resistance, however, the expectation is that diglossia will exert its influence on Scripture use.

The exceptions reported to us thus far can be categorized into the following ‘ecologies of resistance’. These are scenarios where we predict that it might be possible for LL Scripture to be used regularly after NL Scripture has been used:

-

Conflict/Separatism – NL Scripture is in a language associated with conflict/oppression /separatism, the language of a group that is in political or religious opposition or conflict with the vernacular community, or a language that marks a broader identity that the community strongly rejects or is intentionally separating itself from.

-

Limited multilingualism – NL Scripture is in an LWC or prestige language in which the LL community has limited multilingualism (half of the community or less is proficient in it). This could also include liturgical languages, classical languages, LWC’s that are rarely used by the community in daily life, or a national language in the midst of small-scale multilingualism.

-

Large LWC – The LL in question is itself an LWC (or a very large language) one that functions as a language of solidarity and/or identity across a broad region or nation, or one that is accorded some level of prestige within the larger national/regional ecology.

-

Lack of prestige – NL Scripture is in a language that lacks or has lost its prestige, or one that is no longer a target of shift.

-

Church policy – LL Scripture use is encouraged by wider denominational policies/norms, or established by mandates from a centralized church hierarchy (seen often in liturgical churches), or used in pastoral training.

We must be clear that the data indicates these are all exceptions, not the norm. All the cases reported to us of regular vernacular Scripture use occurring after NL Scripture use appear to fall into one of the above scenarios. However, as only one of these scenarios (church policy) has been attested to in our Sulawesi data, research into these exceptions is ongoing. Other ecologies of resistance may come to light as we extend this study beyond Sulawesi.[5]

III. Scope and Methodology

Scope

Sulawesi, Indonesia, was chosen as the area for this pilot study as it is a region where a considerable number of vernacular Scriptures are now available, and the majority was literate in a national language before indigenous literacy/translations arrived (Valkama 1987).

We targeted all of the minority languages of Sulawesi that fit the following parameters:

-

the New Testament is available in the indigenous language

-

the LL translation is at least one year old (to avoid the ‘celebration factor’)

-

the larger indigenous community is not Muslim.[6]

After applying our above criteria to the language communities of Sulawesi we arrived at the 19 languages of this study: Toraja-Sa’dan [sda], Sangir [sxn], Talaud [tld], Tabulahan [atq], Mamasa [mqj], Bambam [ptu], Rampi [lje], Behoa [bep], Bada [bhz], Balantak [blz], Da’a [kzf], Napu [npy], Pamona [pmf], Uma [ppk], Sedoa [tvw], Mori [xmz], Tontemboan [tnt], Seko Padang [skx], and Manado Malay [xmm].[7]

Methodology

Length of survey

Data collection within the 19 language communities was completed via 4 survey trips taken over a 22-month period, from July 2022 to February 2024. Total time spent in villages for this research: 5 ½ months.

Village selection

Our strategy was to always begin our survey in the place of most likely use so as to capture any use that might be present. Author 1 attempted to spend most of his time and collect most of the data in ‘ground zero’, the village where the translator had resided. Usually, the translator and/or his family had lived in that village for several years and had promoted reading Scripture in the mother tongue. So, it stands to reason that the highest rates of use of mother tongue Bibles would be in that village. The idea was that the rates of mother tongue Scripture use in other villages would be lower. This indeed turned out to be the case. The village where the translator resided was the one most likely to use the Bible he or she had translated.

Tools

This survey was mostly quantitative. The unit of analysis was church use of the LL Scripture in worship, supplemented by group use in the home domain (although two of the tools gave some evidence of individual usage as well). Author 1 was the main researcher and conducted the survey in Indonesian. Much of the description of the tools below is based on a previous paper outlining our methodology (Anonby, Simanjuntak, and Eberhard 2024, https://leanpub.com/evidence-based-research).

Multiple tools were utilized to collect the data. This reflects the additional objective within our research project to provide data on scripture use via evidence-based methodologies that do not depend solely on self-report and observation. This set of tools allows for concrete evidence to support reported claims whenever possible via audio and photos.

For data on historical usage of Scripture:

- Historical research

For data on current usage of Scripture:

-

Observation

-

Interviews

-

Recordings of worship services

-

Scripture photography tool

We did not, however, use any SE strategies. We believe it is important not to mix Scripture Engagement activities with scripture use survey so as not to bias the data in any way by suggesting our own opinions as to which scriptures should be used. A short summary of each of our tools follows.[8]

Historical research

To gain insight into past usage of Scripture in these language communities, Author 1 visited local seminaries of the Reformed[9] churches of Sulawesi, the largest branch of Christianity in that area. Via resources found in these seminary libraries, as well as other resources online, various authors provided glimpses of past practices in these churches. Most of these were Dutch authors dating from 1919 to 2001. These sources were: Abineno (1979), Adriani (1919), Aragon (2000), End (2001), Kilgour (n.d.), Nooy-Palm (1975).

Observation

Author 1 spent close to a week in each language community, making sure that he was always there on a Sunday. This enabled him to lessen the observer’s paradox so that more natural use of language could be observed. He usually stayed in the homes of church leaders or local translators. He was present in and observed many church worship meetings in as many denominations as possible during his stay. This included home meetings, which were often several. These observations usually included the language practices of the villages and numerous churches in each language group. Furthermore, it also included observations of oral Scripture use.

Interviews

A total of 85 interviews were conducted. Author 1 asked both laypeople and church leaders various questions related to language ecology. The most important question was, “How many Sundays was the LL Bible used last year?”

Questions that addressed language ecology conditions were highlighted in the questionnaire. Our focus was on the factors that are part of the pre-existing contexts of language ecologies (such as domains and diglossic usage), and how these contexts themselves influence Scripture choice. While Author 1 made it a point to interview both church leaders and laypeople from each church visited, it was found that interviewing laypeople often provided less biased responses than interviews with church leaders/translators, as the latter might feel their reputations or employment to be in jeopardy.

Recordings of worship services

Across the 19 language communities visited, almost 50 separate recordings and 100 hours of audio from both home and church services were collected from various denominations (liturgical and non-liturgical, Pentecostal and non-Pentecostal). These recordings are evidence of Scripture usage on that particular occasion. They were then annotated to identify which parts of the service were in LL and which were in Indonesian, and to allow anyone to locate the Scripture reading in the recording. This is shown by the following excerpt from the Napu language community:

-

17:58–19:20 Scripture reading in Napu

-

19:20–22:19 Baptism ceremony in Indonesian

Scripture Photography Tool

The purpose of this tool was to provide evidence of Scripture usage over time by individuals (either publicly or privately). For this tool, Author 1 took one picture of the outside of an LL Bible, and another of it opened to John 3:16. He tried to ensure the book in question was at least two years old to allow time for some wear. After doing this with the vernacular Bible, Author 1 would ask the owner to show his or her Indonesian Bible and repeat the procedure. He then assessed the condition of each of these Bibles based on the scale outlined below.

Photographs were taken of over 200 Bibles. They were then divided into three categories: (1) unused, (2) lightly used, (3) well used. For example photos of each of these categories, see the Appendix document.

Uses outside church domain

A secondary focus of this study was to look at any evidence of vernacular Scripture usage outside of the church. This included such contexts as small groups, home use, or individual usage. The Scripture Photography tool also provided some evidence of individual use. A Bible that is in pristine condition is most likely not being used either in public or private contexts.

Triangulation

The above methods were implemented in each community to corroborate/triangulate findings. The main tool used to assess Scripture use over time was the set of interviews from both church leaders and laypeople. But at times there were conflicting responses to the question of yearly use from different interviewees. If the church leaders claimed no LL Scripture usage, then triangulation was not critical. However, if the church leaders claimed usage, we would then look at the responses from the laypeople. If these responses were in conflict with those of their leaders, we would then refer to the recordings of the worship service, the presence or lack of LL Bibles in the community, and the condition of the LL Bibles compared to the NL Bibles (comparing wear and tear found in the Bible photos). This evidence-based approach allowed us to corroborate the findings and to provide evidence to help us determine which interview responses were most reliable. In many cases the lay people provided the responses that best matched the other observable data. Often, one final interview provided a story that would finally make sense of all the data.

Calculating Use

The numbers on LL Scripture usage in Table 1 are derived from asking questions of members of every church in ‘ground zero’ (the place where translators lived or the target location for the translation). These questions would ask about the frequency of LL and NL Scripture use in public worship over the span of last year. Table 1 compares the number of Sundays per year that the LL Scripture is used versus the Indonesian. The numbers are an average of Sundays across all churches in all denominations in each particular community. This average is an estimate based on usage in ground zero.

Our calculation for usage across a whole language community was arrived at via five steps: 1) identifying all the denominations found in ground zero, 2) interviewing members from each of those churches to get the amount of usage in that denomination in that village (triangulating those responses with observations, audio recordings and Bible photos as needed), 3) counting the number of churches of each denomination in ground zero and multiplying that by the number of villages across the whole community to get a total number of churches per denomination. 4) taking the usage of each denomination in ground zero as the assessment for usage of that denomination throughout the community as a whole. 5) combining the usage of all the denominations and then dividing by the total number of churches to arrive at an average # of Sundays per year for each community. Because the estimate is an extrapolation of usage based on ground zero, the community results will most likely err on the generous side as usage would be expected to diminish as one gets further from the ground zero location. For example, around 50% of the Sangir churches were Reformed. Of these, it was reported that they used the Sangir Scripture once a month. That would mean among the Reformed churches, they used the LL Scriptures 12 times a year, and exclusively the Indonesian Scriptures 40 times. But if we include the non-Reformed churches which almost never use the LL Scripture (averaging 1 time per year), the percentage of LL Scripture use throughout all the churches decreases to roughly eight Sundays per year.

IV. Findings

Language use in the Christian context

Use of the Vernacular Scriptures

When asked how often the local language Bible was used in church, by far the most common response was once a month. However, closer investigation revealed the answer was much more nuanced. For example, some Pentecostal congregations reported using the vernacular every few years, while others were not even aware there was a Bible in their language. There was also a great disparity between Reformed congregations. For example, in many communities there were only one or two churches which followed the Synod’s rules of having monthly services in the language. Case in point among the Mori, there was one Reformed church (out of 49) that had monthly services in the vernacular.

But even in the special services in the LL, most of the time the announcements are in Indonesian. It seems to take extra, advanced planning to conduct services in the vernacular. People usually have to spend hours practicing singing or reading Scripture. For example, when we were in Sangir, Easter Sunday fell on a designated local language day. But they told us that planning a holiday service in the language would be too difficult, so they used Indonesian.

The use of vernacular Scripture in church is rarely spontaneous. Instead, reading LL is something of a performance. For example, one of the activities in a youth rally was a Sangir Scripture reading competition. In another instance, a Tontemboan native language service was delayed half an hour late as the leaders practiced their lines in a neighboring room.

One clear indicator of the lack of use of the vernacular Bibles was that they were often locked up or otherwise very hard to find. In other places, such as among Manado Malay, many people weren’t aware of the existence of a Bible in their language. In Manado city, Author 1 visited a large Christian bookstore. Though there were many shelves of books translated into Indonesian from English, there were no Bibles in Manado Malay.

In the 1980s, Aragon (2000, 177) noted how the Uma expressed great pride in having Scripture in their language, yet in all her years of fieldwork, she never saw them use the book. Forty years later, Author 1 found many of the same attitudes and behaviors. Many knew details about how and when the Bible was translated. However, when Author 1 asked to photograph the Bible they were talking about, the book would frequently be unused, often still wrapped in plastic. Observations such as these gave us the impression that many thought of vernacular Bibles as precious artifacts, to be given to friends or carefully stored.

The situation was similar with non-print media. The Sangir, Napu, Uma, Manado Malay, Bambam, Mamasa, Bada, and others expressed great excitement about having their Bible in electronic form. However, non-print media seemed to be used even less than print. Only on two occasions did Author 1 witness someone reading the vernacular Bible on the phone in church. Most people hadn’t downloaded the app yet. Those who had sometimes took up to fifteen minutes to find a verse. All were able to find the Indonesian Bible on their phones more quickly. It was almost the same situation with the Jesus Film, which had been translated into several of the languages we surveyed. People were very enthused about the technology and were eager to talk about how enjoyable the dubbing process had been. But Author 1 only saw the movie watched once, by a Talaud man in his living room.

Reasons for using the vernacular

In most liturgical, Reformed churches, the use of the LL Scripture in church worship was mandated or encouraged by the Synod. It was a common denominational policy to use the LL Scripture once per month. The actual practice on the ground was usually much less than that. Also, when people read vernacular Scripture, it was usually followed up with reading the same verse in Indonesian.

A common rationale expressed by leaders and congregants was that the LL Bible would help with language preservation. Almost all groups said they were concerned that the vernacular was being lost and believed having the Bible in the LL would preserve the language or encourage young people to learn it. In this sense, the LL Bible was a symbol of group identity.

In some locations, Author 1 was told the reason they used the local language in services was because the congregation, particularly the older members, understood it better. However, most older people Author 1 interviewed claimed the custom of reading in the vernacular was less about being considerate to them, and more about following the Synod ruling. Almost all the people who claimed they understood the LL Bible better were translators.

Another reason for Bible translation was financial. On several occasions, Author 1 had people approach him and recommend a friend or family member for a paid position on the translation team. In other cases, he had people talk earnestly about the need for Author 1 to sponsor the translation of the Old Testament, and express desire to be employed in the process.

The villages that use the most LL in church were invariably the ones most closely associated with the translators. Some of these hotspots reported much higher use of the vernacular Bible than average. For example, on Salibabu Island, there was one village that reported using the Talaud Bible twice a month, versus the average of once every three months.

Reasons for not using the vernacular

Though Author 1 never asked people why they did not use the LL Bible, they frequently volunteered various reasons. The most frequent was discomfort in reading LL in public. In the vernacular language services, Scripture is usually read in both languages. Author 1 noted people always read Indonesian more fluently than their LL. Another reason given was lack of access to the vernacular Bible. Sometimes, people claimed dialectical differences impeded their understanding of the LL. Finally, there was the matter of appropriateness. Some groups, like Manado Malay speakers, felt it wasn’t proper to read the Bible in what was seen as more of an informal lect.

It may be that the most significant reason is simply that their needs were met by the Indonesian Bible. In the majority of the areas, people told Author 1 they understood Indonesian better than the vernacular. Some used the Indonesian Bible to help them understand the LL. So, it seems likely that lack of comprehension is a motivation for not using the LL Scripture. However, even in the areas where the vernacular languages were very strong, the LL Bible was rarely used. In these cases, lack of LL use was not because the people didn’t understand it. A more plausible explanation is that they had gotten used to having Scripture read and explained to them in Indonesian.

All of the above points to one conclusion - once a congregation becomes accustomed to reading the Bible in a NL (in this case, Indonesian), they very rarely switch to using Scripture in the LL.

Results on historical usage

The Toraja, Pamona, Sangir, Mori, Talaud, Tontemboan, Bada, Napu and Uma were first educated in their LL. This was because this group of tribes were evangelized early on, and the first missionaries believed it was very important to communicate in the local languages (Aragon 2000, 103; End 2001). In keeping with this policy, the Bible was translated into several Sulawesi languages in the nineteenth century, after attempts at using Malay translations failed (End 2001). By 1896 many tribespeople had learned how to read in their native languages (Adriani 1919, 96, 135, 168, 170, 173, 231).

After independence, the schooling system became more widespread, and only used the Malay language, which was re-christened Indonesian. Starting in the 1980s there was an effort, primarily spearheaded by SIL, to begin translating New Testaments into the indigenous languages of Sulawesi (Aragon 2000, 310). In the 1970s and 1980s, SIL linguists allocated in several villages began translating the Bible into the various indigenous languages (Aragon 2000, 310). But by that time, Malay had been the only language of literacy for one or two generations.

By the early 2000s, a large number of vernacular translations had been completed and by the mid 2010s, many Reformed synods had begun urging their churches to use these newly translated Scriptures. Today, the upper leadership encourages monthly in the indigenous language. But while there is evidence of many churches that have switched from their native language to Indonesian, there are no examples of congregations who have switched back to using their native language as the normative text for public reading. LL Scripture reading almost exclusively occurs in special cultural services mandated by the church hierarchy, and these are held quite sporadically.

Results on current usage

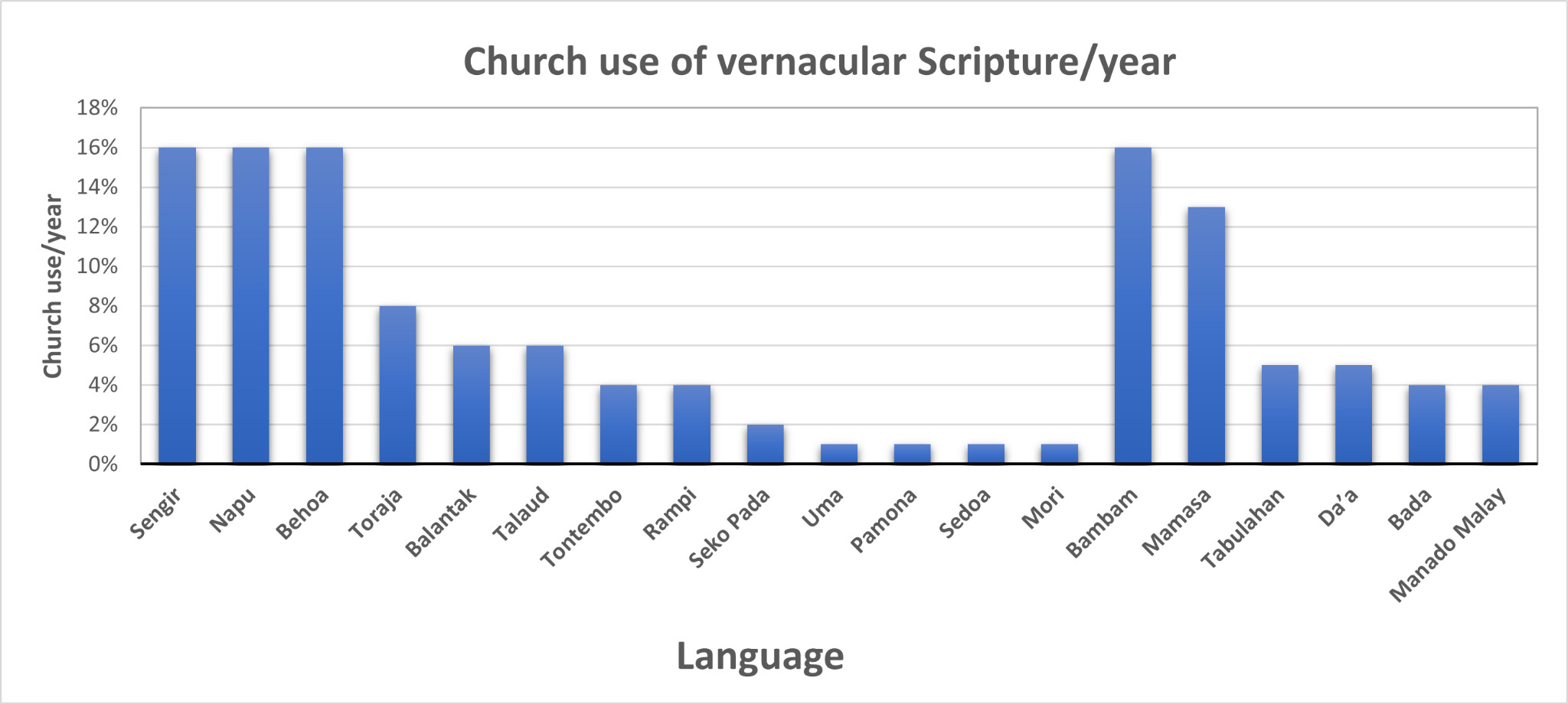

All the tools showed very low levels of LL Scripture usage across these 19 Sulawesi languages. The results of observing and making audio recordings of worship settings were supplemented by interviews of parishioners to get a long-term understanding of use. Although Author 1 did observe vernacular Scripture usage in weekday group meetings as well, the phenomenon was vanishingly rare. Since midweek use was much less than Sunday use, the metric we utilized was the percentage of Sundays per year that a given language was used for reading Scripture in public worship. We found an average of 7% usage per year across the various churches among the 19 languages we studied in Sulawesi. The percentage of yearly usage of both the LL and the NL Scriptures in each language community is shown in Figure 2 and Table 1 below as an average across all churches in all denominations.

The following table compares Indonesian and vernacular Scripture use based on Sundays per year.

Liturgical churches use more vernacular Scripture than their non-liturgical counterparts. The percentages in the following data do not coincide exactly with the graph and table above because each community had a different percentage of liturgical and non-liturgical churches. For the strong languages (EGIDS 6a–3), liturgical churches used LL Scripture 9% of the time (roughly 5 Sundays per year), while non-liturgical churches used LL Scripture less than 1 Sunday per year. Among the weak languages (EGIDS 6b–7), the liturgical churches also used LL Scripture 9% of the time (roughly 5 Sundays per year), while the non-liturgical churches did not use it at all.

The results of the Scripture photography tool were as follows. In all there were 8 well-used LL Bibles and 61 well-used NL Bibles. Of these, the breakdown of well-used Bibles was:

-

Weaker language: 4 well-used LL Bibles, 38 well-used NL Bibles.

-

Stronger language: 4 well-used LL Bibles, 23 well-used NL Bibles.

These results show that across the 19 language communities, LL Scriptures consistently showed less signs of usage than their NL counterpart. The vast majority of the LL Scriptures were in pristine condition, with no signs of wear.

Home Use

Author 1 attended many home meetings in Christian communities in Sulawesi, participating both in celebrations and Bible studies. In most home meetings everyone came with only an Indonesian Bible. Author 1 found LL Scripture reading to be very rare and often done for his benefit (or so they told him.). Also, when they didn’t tell him specifically, their eyes were often on Author 1 as the vernacular Scripture was being read. One reason the LL may be used in the home is if there is an ongoing translation project and the meetings are hosted by the translator. In fact, the only occasion where Author 1 observed an actual group of people studying or reading from the vernacular Scriptures together was in a Bible study at the Bambam translator’s home. In almost all the home meetings Author 1 attended, the entire service was in Indonesian. In fact, there was a lower proportion of LL Scripture use in homes than in Sunday morning church services.

This means that in Sulawesi, not only are the LL Scriptures not being used in the churches (aside from a token cultural identity marker), they are also not being used in the home. This contradicts much of the current assumptions about LL usage (Russell 1936). It has always been the case that most Christians around the world get the majority of their exposure to Scripture from the public reading of the Bible in church settings. If this is true of highly literate societies, we should not expect it to be any different among the less literate ones.

V. Analysis

Addressing research question 1

Interview data, observation, audio recordings of services, and the comparison of the photos of LL/NL Scriptures all confirmed the current use of the LL Scripture is minimal across the predominately Christian groups in Sulawesi. Observations of informal home meetings in the villages found that usage in the homes was even less than in formal services. The four groups with the highest usage are the Napu, Behoa, Sangir and Bambam.[10]

Here is a summary of the major findings related to the state of Scripture use in Sulawesi:

-

The combined percentage for LL Scripture reading in all churches was 7%.[11]

-

The use that does happen occurs in liturgical denominations that mandate or encourage it.

-

Most Reformed congregations use the LL Scripture much less than their synod recommends.

-

The average LL Bible was unused, while the average Indonesian Bible was well used.

-

There was more LL usage in church meetings than in home meetings.

There were numerous factors that did not appear to have any effect on Scripture use:

-

There was no difference in usage between languages with strong and weak vitality.

-

There was no significant difference in usage between old and new translations. Fifteen of the languages had New Testaments translations completed in the 2010s. The usage of LL Scripture among these fifteen was just as minimal as that found among those who received vernacular New Testaments in the mid 1900s.

-

There was little difference in usage between groups who had Scripture engagement and those who did not. For example, the Tontenbaum, Da’a, Tabulahan, and Toraja all have had people working in Scripture engagement. However, these efforts have not resulted in a higher rate of LL usage.

The one factor that did make a difference was whether or not the congregation belonged to a liturgical church. Most of these had some LL Scripture usage (averaging 9% per year), while the other congregations used LL Bible less than 1% of the time. Usage of LL Scriptures in liturgical churches appears to be motivated more by an identity function than felt spiritual need. This last insight was based on the fact that in many Sunday worship services where LL Scripture usage was witnessed, this usage was accompanied by numerous other cultural markings such as traditional dress and more LL music. These cultural trappings were much less common during ‘regular’ worship services. This leads us to believe that vernacular Scripture usage is motivated more by an identity function than a spiritual one. (See the Conclusion for more on this insight.

Addressing research question 2

Although the sequencing of translation hypothesis cannot yet be proven true or false from our Sulawesi data alone, the answer to research question 2 from our Sulawesi data is clearly negative. In the communities studied, none of the vernacular Scriptures have become the normative Scripture in public worship settings after NL Scriptures filled that role. Furthermore, we found that where LL Scriptures were used first, they were eventually replaced by Indonesian.

Nevertheless, there is evidence in Sulawesi of the sequencing of translation being an influence on LL Scripture usage in the past. 9 of the 19 communities had LL Scripture portions translated early on, before the spread of Indonesian literacy that followed the national independence in 1945. These were the Bada, Toraja, Pamona, Sangir, Napu, Uma, Mori, Tontemboan, and Talaud groups. While a non-standard form of Malay was used as an LWC in coastal areas as early as the 17th century, multilingualism and literacy in Malay did not become widespread in the highlands of Sulawesi until after 1945. Comments made by the authors listed in the sources below suggest that these vernacular portions were most likely being used until they were replaced with the more prestigious Indonesian Scriptures that came after independence.

Further evidence of early LL Scripture usage in some of these groups comes from our observations and photographs of early gravestones with indigenous language texts on them. Photographic evidence of early LL text on gravestones (much of it in the form of LL Scripture) predating the expansion of Indonesian was found in the following language communities: Sangir, Toraja, Pamona, Mori, Bada (see our photo database).

Even though all eight of these ‘LL first’ churches are now using the NL as their normative Scripture, there was a considerable period when their LL Scriptures were the only Scriptures used, some of them for over a century. This would suggest that the lack of multilingualism and diglossia was indeed a factor influencing the usage of LL Scripture in the past. This pre-diglossic period might prove to have been the greatest window of opportunity for vernacular Scripture use in Sulawesi.[12]

What is missing in our Sulawesi data are examples where the LL Scripture arrived first and where it continues to be a normative Scripture in use today even after the introduction of the NL Scripture. This type of data would strengthen our sequencing of translation hypothesis. Our investigation of this hypothesis will continue to be developed in future studies in additional countries and the combined results addressed in a concluding paper.

Exceptions in Sulawesi

Our findings also indicate that one of the exceptions to the sequencing of translation predicted at the outset of this study does exist in Sulawesi. This ecology of resistance consists of the liturgical churches that use LL Scripture in a limited fashion in spite of diglossic pressure. In four of these communities (Napu, Behoa, Sangir, and Bambam), the liturgical churches reported usage of LL Scriptures roughly once per month (alongside readings in Indonesian). Overall, liturgical church members report an average of approximately 5 Sundays (or 9%) of LL Scripture usage in public worship over an entire year (see Table 2). In each case this usage was reported by church leaders as something either mandated or at least encouraged by church policy. This is a strong confirmation of the existence of exception 5: “church policy.”

VI. Conclusion

Impact on BT past and future

This study has both past and future implications for the task of Bible translation. Our evidence shows that, on Sulawesi, none of the LL Scriptures studied have become the normative text in worship. Our sequencing of translation hypothesis, if it continues to hold after applying it in other countries, has the potential to provide an underlying explanation for why many completed Bible translation programs have never seen widespread indigenous Scripture usage in church.

Improving our understanding of the link between diglossia and translation will also potentially help BT agencies plan for the future. Once we have been able to apply this research in a broader number of countries and languages, we will be able to suggest a set of recommendations for future translation starts. But our Sulawesi data alone strongly suggests avoiding new translations in situations where there is already an existing church using a national language translation. Such scenarios show extremely low levels of vernacular Scripture usage in Sulawesi. This new understanding could become useful when assessing the viability of new translation projects and more effective ways to allocate resources. We will continue to report on the impact of the sequencing of translation as our research grows, and as our data set becomes more robust, covering more types of ecologies.

A Final Word: Some thoughts on human flourishing

We would like to close reflecting on the idea of human flourishing, and how these findings speak to that. In recent years, human flourishing/thriving has been adopted as one of the main objectives within the Bible translation movement. This is based on a recognition that the Bible, in any appropriate language, contributes to all of life and has wide benefits. Also, peoples with access to Scriptures are more likely to adopt the Christian faith.

Bible translation organizations that include the notion of human flourishing in their vision statements often do not preclude the use of the NL in indigenous communities or their churches. However, the application of Bible translation strategies on the ground has generally focused on those benefits associated with the use of the vernacular Scriptures alone. Any flourishing that may come as a result of use of the NL scripture has largely been ignored by the BT movement and even questioned by some within the various organizations. However, our survey suggests that it is possible for multilingual minority language communities to not only come to Christian faith via a NL Scripture, but to show signs of growth in faith via those same scriptures. We observed that most of the Sulawesi churches studied are large, well-attended, with active youth groups, supporting their own pastors, and reaching out to their communities. In these ways they surpassed the original metrics established by Venn and Anderson (Warren 1971) of what constitutes an indigenous church — self-propagating, self-governing, and self-supporting. And in every Sulawesi church studied, the Scripture most associated with the journey of Christian faith was the NL. This suggests that other areas of communal health and thriving may also be associated with the NL, and a new look at the connection between language and flourishing at the community level may be in order.

In Sulawesi, the use of the NL scripture is not found in isolated cases but rather has become the most common means by which indigenous churches practice discipleship and experience growth. Taking the idea of flourishing seriously requires us to acknowledge that indigenous communities flourishing in the NL is not just a possibility, but it could be prevalent in many regions of the world. It also brings with it a critical awareness that the goal of ending worldwide Bible poverty is closer to being realized than previously thought.

Abbreviations: LL = local language, NL = national/regional language, BT = Bible translation

While ‘Freedom to commit’ is a major factor in Scripture usage in some ecologies (such as strong Muslim areas where Christian churches are prohibited), it is a given condition that affects the usage of both vernacular and national language Scripture alike. For that reason, we will not address it any further in our attempt to understand why national language Scriptures are used more than local language Scriptures in many communities.

Language vitality is another factor that sociolinguists would consider an important and even obligatory support for the use of vernacular literacy. Language shift clearly undermines any attempts at LL literacy, a principle that has been encoded in the EGIDS scale (Lewis and Simons 2010), where there is a hierarchical relationship between sustainable literacy and sustainable orality, with the former being built upon the latter. However, we discovered that there are communities who do use their vernacular Scripture (to a minimal degree) even though their local language is undergoing shift. Furthermore, strong languages and weak languages in this study performed the same in terms of LL scripture usage. Since our goal is to capture and assess all possible cases of vernacular Scripture use, we will not be limiting ourselves to high vitality languages.

Some of the previous VSU studies have combined Scripture engagement activities with Scripture use assessment. While much enthusiasm for LL Scripture has been generated in these efforts, we believe it is difficult to get unbiased responses when assessing the languages people are using for Scripture while simultaneously promoting one of the languages involved. Our VSU research methodology focuses only on assessment, intentionally avoiding Scripture engagement activities or any communication or action that might suggest any language preferences of those doing the research.

Beyond these broader ecological factors, there may also be situations where specific individuals or agencies who were part of the translation team/process are pressuring or influencing the practices of local churches such that the local church is not making its own decisions about Scripture use. Evidence for this might be when the only church using the LL scripture is the one where the translation team member attends. Similar influence could come from outsiders conducting Scripture engagement activities in local churches. Such cases are not included in our ‘ecologies of resistance’ as they could easily influence community choices.

Author 1 was restricted from surveying language communities in which the majority religion is Islam.

While Manado Malay is an LWC in Sulawesi, we included it in our study to compare its usage to that of the local language translations.

Links to the datasets of results from these tools (with interview responses, audio recordings, and Bible photos) can be found in the Appendix.

In this paper, the use of the term Reformed church(es) will be referring to any one or all of the Calvinist denominations with their synods in Central Sulawesi Province: 1. Gereja Protestan Indonesia Donggala (GPID) 2. Gereja Kristen Sulawesi Tengah (GKST) (GKST is the biggest synod in Central Sulawesi) 3. Gereja Protestan Indonesia Buol Tolitoli (GPIBT) 4. Gereja Kristen Luwuk Banggai (GKLB) 5. Gereja Protestan Indonesia Banggai Kepulauan (GPIBK)

Two factors that may be influencing a slightly higher use of the LL among these 4 groups: 1) An influential leader that embraces the LL translation — (e.g. Sangir) 2) Members of translation committee still translating and influencing usage of LL — (e.g. Bambam).

This data comes from northern and central Sulawesi where the predominant liturgical congregations are those of the Reformed denominations. Via observation and interviews, Author 1 found that the Catholic congregations in this region did not use the LL Scripture. In Southeast Sulawesi, however, René van den Berg (p.c.) reports 50% usage of the Muna Scripture in a Catholic parish consisting of 7 congregations.

This parallels to some degree what we have seen in Brazil. According to personal observations and discussions with the translators involved, all of the Brazilian LL Scriptures that are being used widely in their churches today were the first Scriptures ever used by these communities. These are the older translations such as the Guajajara, Kayapó, Waiwai, Sataré-Mawé, Apalai and Xavante, all of them done before Portuguese schools became widespread in those indigenous areas. The first portions of Scripture ever seen in these communities were in the LL. The difference between these Brazilian cases and the nine Sulawesi communities above is that these six groups in Brazil are characterized by strong group identities that have been resilient enough to resist change and continue normative use of their LL Scriptures even after the NL Scriptures arrived.

.png)

.png)